Dear friends,

It’s complicated here in this Bardo, this world between worlds that we call 2021. Like any animal emerging from a cocoon or hibernation, many of us are tender and tentative. As we take each step toward “normal,” we ask ourselves, Now where was I? (in the Before World). But in all the excitement, we can easily forget to ask Who am I Now? No longer in the old safe world of traditional etiquette, we’re on our own to find some graciousness as the world keeps changing. Daily. Mask on or off? How to come up with safety agreements with people we love who nonetheless disagree with us on the red-hot subject of vaccinations?

Decision fatigue alone is enough to make you want to crawl back into lockdown. There’s no One Size Fits All, and we’re on our own to fashion something that works each time we engage with our families and friends. Even if we figure something out, there’s no guarantee that things won’t all change again. Quite the opposite. This requires a flexibility and equanimity I’m only beginning to feel in this life. If we were butterflies emerging from the cocoon, we’d flap our new wings before flying into this new world. The human equivalent is to take that second question about who I am now more seriously. To take time to adjust to this new reality before taking a giant leap back OR forward in this Simon Says world of the pandemic.

Sometimes when I need perspective I look to my ancestors for inspiration. I found some by going all the way back to the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1870. My great great grandmother Maria Raum, a new immigrant, lost her husband and an unborn baby to the Yellow Fever plague in Memphis after his beer wagon was commandeered to remove bodies. Maria was left penniless and unable to feed herself and her 3 and 5 year old daughters. Unable to go back home to Germany, unable to speak the language of the new world, she did what she had to do so that they would survive. She sent them off to a Lutheran orphanage while she worked as domestic help and saved enough money to be able to support them. After three years she emerged from the world of pandemic domestic service to find they had been packed up and loaded onto an Orphan Train headed west. Hundreds of miles and inquiries later she found them living with their new farm families.

What she did next is my favorite page of family history. Instead of fighting to reclaim her girls, she and her new husband built a house down the road to watch them grow and have children of their own. She’s buried in a small German cemetery near her daughters and their adoptive families. Now that’s a radical form of resilience, an example of true Motherlove.

I call on this grace and resilience as I dream of what this next world might become. I’m beginning right here, where I am today, dreaming this new future, knowing even if it all changes love will find a way. Always does in the end.

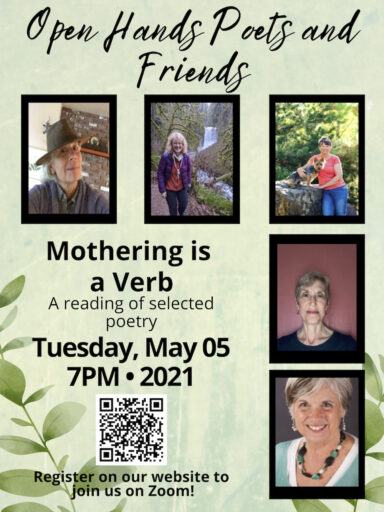

PS. I’ve been writing more poetry during our current pandemic. I’ll be reading this new poem about my mother’s mother’s mother, this week, along with my Open Handed Writers’ group and friends. It’s a free Zoom call (with the support of our local bookstore)

PS. I’ve been writing more poetry during our current pandemic. I’ll be reading this new poem about my mother’s mother’s mother, this week, along with my Open Handed Writers’ group and friends. It’s a free Zoom call (with the support of our local bookstore)If you’re reading this May 5th, come listen tonight at 7 PT and join us as we celebrate Mothering as a Verb. Just visit this page for the link.

Dreaming DaughtersThe women in my family dream their daughters,And so I dreamed you up, a strong Baby Woman.Just as my mother dreamed herself a sister instead of a babyAnd her mother dreamed a prodigy, Shirley Temple of Saline County.And her mother before her dreamed up a milliner.But the mother before that, a new immigrant turned into a widow by Yellow Fever,That mother just dreamed of getting her daughters’ bellies fedAnd so she let them go by boat to an orphanage,signs hanging from necks in the only language she knew,saying keep them safe and I will come.And when she didn’t, couldn’t, an orphan train took themTo new farm families with mothers who at least spoke the old tongue,who adopted them and who fed themand put them to work cooking for farm hands untilthey began to have dreams in this strange, new languageand when their German mother traveled hundreds of miles to find them happy,she built a little house the size of her new dreamdown the road from their full-bellied lives.But she just kept on dreaming and watching in that new placebecause that’s what mothers do sometimes.